I blogged about the 2015 Gibson offering and their crazy ‘Robot tuners’ some time ago. I argued that the CEO Henry Juszkiewicz had taken a massive wrong turn with current designs and that their U turn had been an inevitable outcome of that.

But the real truth is that Gibson (and possibly to a smaller degree Fender) appear to be in serious trouble, and in part this is a product of their own making.

Gibson and Consumer Electronics – Diversification in a shrinking market:

Back in 2014, Gibson acquired Phillips consumer electronics arm (the strangely named ‘Woox Innovations’) for around $140 Million. Gibson’s intent was to move from being a guitar company to being a ‘Global Leader In Music & Sound’. It had already bought other electronics industries such as Teac, and owned Cakewalk/Sonar.

I was alerted by a news story that popped up yesterday again, that Cakewalk was to be shuttered, all development of the Sonar platform was to cease, to have a wider look at the Gibson situation and the underlying issues with not just them, but the music biz in general.

Leveraged growth

Do you remember the story of Tower records? It went stellar in the late 70’s, expanded way too rapidly into the 1990’s, and then found that there was no real way of paying back the money it had used to expand? It collapsed under a ton of debt and red lines.

Gibson is facing similar issues. In the mid 80’s, it was dying in the hands of the Norlin Corporation who seemed to know about as much about making guitars as I know about nuclear physics. HJ led the takeover and by the mid 90’s had not only turned the company around, but had it making the best guitars it had made since it had fallen out with Les Paul in the 1960’s. (I have a ’96 – its a great guitar- my main squeeze until I started building).

Gibson saw the reduction in guitar sales as a cue to diversify. Electric guitar sales have been on a steady decline for years, in the USA down by about a third over the last decade. There are multiple reasons for this, but I’ll return to those later. So the desire to diversify doesn’t on the face of it seem so strange. But its how they achieved this that has run them into trouble, in that they had to leverage their acquisitions quite heavily.

Early this year, they had to restructure a part of their debt. That amounted to taking on about $185M of new liabilities, but created liquidity for the company to be able to get on with the day to day business, rolling over in the process about $100M of looming repayments.

Moody’s just downgraded Gibson Bonds – (a debt creation tool, where the company takes money for a promissory note to pay the bond back with interest at a fixed date) – to Caa1. This is Junk status, actually way deep in junk status. Gibson notes (which pay their interest regularly like any other bond but don’t return their capital until the due date) are trading at well less than their face value – last I saw about 59c on the $. That suggests that investors are willing to lose some now to avoid losing more later, if Gibson defaults. The ‘market’ rates that at about a 40% chance. There’s some good research on the numbers by Eric Garland here.

Then according to reports there’s another load of debt due in August 2018 – Eric thinks about $375m, but other reports say more like $500m plus. Whichever is correct,we’re talking telephone numbers.

Inside the Corporation

So why are Gibson still haemorrhaging cash and losing market share, and why hasn’t diversification helped them? One reason is that they haven’t bought wisely, and their acquisitions aren’t fast growing enough or cash producing to cover the debt that they incurred. And that also their businesses aren’t very joined up. Too much, too quickly.

But another reason must be the culture at Gibson, which is an issue that would by all reports seem to start with HJ himself.

The CEO appoints all staff, personally. He micromanages at every level of the company. At the same time he has made some quite unusual decisions. (Who can forget the Firebird X model, or the dayglo Les Paul?) The 2015 Les Paul Standard range was a response to a number of production issues that had began to creep in – fret edges grabbing strings into the binding, poor tuning, etc. Rather than working this as a quality control issue, the decision was made to widen the necks and add a brass nut to replace the poorly cut Corian.

Then there’s the output itself. The credit ratings agencies have said that one issue with Gibson is that they have too few product lines, and that the product lines are decreasing. However, this is the opposite of what the customer is saying. What they want is good historic standard guitars, at a price that the working musician can afford. Evolution, not revolution. Gibson, for all its faults, is being puled in two directions by competing interests – guitarists and fund managers.

So they have closed Cakewalk – I assume that they thought this quick end would be less expensive than trying to sustain it while it was sold, and they might be right as DAW is a crowded market. But they are making other changes. The Crimson Custom shop has been quietly closed too, for how long it is not clear. The founder of the Custom Shop line apparently has moved on. The Nashville factory is up for sale, with Gibson planning to move out of there after a time to new facility in Nashville that they also don’t plan to own.

There’s a website that rates companies from a workers perspective – Glassdoor. I signed up so that I could have a look at what the staff thought of it. I have never seen a worse public profile for a business in a high spec production environment in the West! It’s employees seem to hate it, and they don’t seem to stay long. In fact, the culture is reportedly so toxic that managers seem not to last long at all, creating a disjointed feedback system to the top of the issues in production and quality.

Hours are long, relations with management poor, benefits pretty low and pay not much better for the level of skill involved. Output figures chased with relentless pressure, supervisors constantly moved about, a loss of personality. The shop floor workers report a great degree of solidarity with each other, but none with those above them.

Gibson, like Norlin before it, would appear to have become a numbers game, not a quality one, if the reports are to believed. Higher and higher output with less and less regard for the quality of the items delivered seem to be the antidote to rising debt. Now of course, reports from the shop floor like this, anonymised, should be treated with caution. But there are hundreds of them, and clearly there are some pumped responses that are so transparently management trying to alter the stats that it’s almost laughable.

Henry is just not listening, and nobody seems powerful enough to question his wisdom.

Out on the Street

Out on the street, something is happening in the music industry. The independent retailer is disappearing. And the ones that are there often don’t stock Fender and Gibson from the factory. Second hand, yes. But not new.

The Music industry is being distorted by venture capital. Mergers and Acquisitions are a way of creating economies of scale and rapid expansion, but they are having another effect. As FMIC and Gibson have grown in size bringing in many of the previously independent manufacturers, they have also changed their sale model into the retailer. They no longer use distribution companies. Those companies gave the independent retailer an opportunity to stock the big brands, because they also had accounts with them for consumables – strings, sticks, heads, spares, accessories, and some of the less exclusive brands. Gibson used Rosetti, Fender for years traded in the UK via Arbiter.

But when they cut out the middle man, they also cut away the independents. They raised capital investment and minimum inventory holds for the stores. Then when they made disastrous product changes they discounted heavily through online retailers to shift unwanted stock, leaving many independents with massive losses to bear on unsellable items – items which they had forced them to stock against their better judgement in the first place. Many of those that survived the 2008 crash and the collapse in demand, simply walked away from Fender and Gibson (and the brands they also own).

That restricted the visibility of the big brands to the big chain stores, but also their feeder brands like Squier and Epiphone. But not all of those big boys have fared well in the past few years either. They bought into huge numbers of brick and internet platforms. Competition became fierce and margins fell, taking Soundcontrol with it in the UK. In the USA, Guitar Center teeters on the brink, massively leveraged and a mere showroom for the low end Internet sellers that the Guitar companies are now supplying (including Amazon!) When you walk into these stores now, where once they were alive with the sound of guitarists trying out new gear, now largely there are three or four guys behind the counter, outnumbering the customers 2-1. Piped music plays in the background.

To keep visibility and find new sales, both Gibson and Fender have ventured online at prices which undercut their own dealers, especially the independent ones, causing even more to walk away from the brands. But would you drop £2500 for a guitar online? I wouldn’t. It’s a risk.

Culture wars

In the UK and the USA the culture has shifted significantly in music as in many other areas in the last 20 years. Yes the X Factor type TV shows have caused some of it. But some of it comes from the immediate nature of life itself in the technology age. Kids can gain instant gratification from Computer games and other technology. Learning to play is becoming less popular. It’s slow, can be difficult, and requires patience. And those who do learn in the school system are often squeezed into the ‘Rockschool’ system which if misused can stifle individuality and therefore the desire to continue into adulthood.

But there is another significant issue; who is the next guitar hero that will ignite a million fingers? In the last ten years, that guitar hero has been…….Taylor Swift.

Yes really!

Back in 2004/5 when I returned to full time music after 12 years out in industry, it was Billy Joe Armstrong. But at the end of the day, neither of them are ‘great players’ in the vein of Hendrix, Van Halen, Clapton, Vai, or even the early players like Charlie Christian, Jango, B.B. King or Scotty Moore. You might learn to play based on the modern guitar heroes, but you’ll never really open up the possibilities of guitar playing Punk or Pop. The only players pushing the envelope are in the fringes of prog, jazz and metal, which get no airtime.

That is the real reason why the electric guitar market is shrinking and the only growth market is in Ukelele and budget acoustic instruments. The majority of kids get where they want to go fairly quickly, or get bored and drift away. And because their target is quite low, there’s less chance of them playing into adulthood because the satisfaction is also lower. Fender are reportedly trying to combat that by creating online courses that come with their guitars in the USA. The realisation that they won’t sell their top end products to a new generation unless they can nurture them and keep them in the game for a number of years has become apparent to them. You won’t buy an expensive guitar where a cheap one will do, and only when you have matured as a player will you pay out for a ‘Made in the USA’ premium instrument.

Meanwhile, my custom build customers over the last two years have all been in their 50’s or above. Many of my repair customers are the same. Younger students seem less abundant, the desire is less than it was ten years ago, and they buy and sell cheap guitars but never invest in that lifelong instrument. Always tinkering, but never settling. The high end customer base is ageing fast. And they already have their ‘lifetime Guitar’ in most cases.

If there’s any growth in the electric guitar industry, it’s in the heavy drop tuned 7 and 8 string market. But these aren’t really premium instruments in many cases just as the 80’s spank planks I played in my youth often weren’t, and they aren’t something that either Fender or Gibson do much trade in. that is in the mid priced pointy end of the far Eastern Market, and its doing fairly well by all accounts. And when my younger students come in and ask to to learn a specific song now – the chances are it will be Offspring, Blink 182, or something far heavier that I’ve never heard of. If not that, its an acoustic song in a non standard tuning. Mainstream music is not guitar driven any more. The next Ace Frehley is not just around the corner.

So where does the industry go from here?

In Gibson’s case, unless it can restructure its debt next year there is a possibility that it will be broken up. The most valuable part will be its intellectual property in the Brand itself, and the historic models that encompasses. There’s a lot to work with for the right investor, just as there was when Norlin finally gave it up in the 80’s. But they will have to understand that the market is unlikely to grow significantly now, and that they must offer better value.

Fender seem in much better health, but they still face the same issues on a much smaller scale. Their current modern series of American Standards have not set the world alight. and this after in a similar time to Gibson having come back from the brink when they rose from the CBS era. But they have a wider portfolio into budget instruments, and a more solid one. If Gibson production were to end in the USA though, Fender would surely look at that and have to make a decision as to whether they would need to compete on the ‘made in USA’ badge. Mexico would invite an uplift in production I suspect.

Even PRS have apparently reduced production at the top end, and increased the Korean range. At the same time, in the UK they supplied new standard model instruments to retail to a company that is essentially a Pawn Broker. I nearly fell out of my boots when I saw that a few years ago.

But the real lifesaver for the guitar industry will be a new hero to come along and ignite the imagination. And every guitar maker, large or small, will hope that it’s their guitar around that hero’s neck.

In the end, that’s what we do – We’re in the imagination business

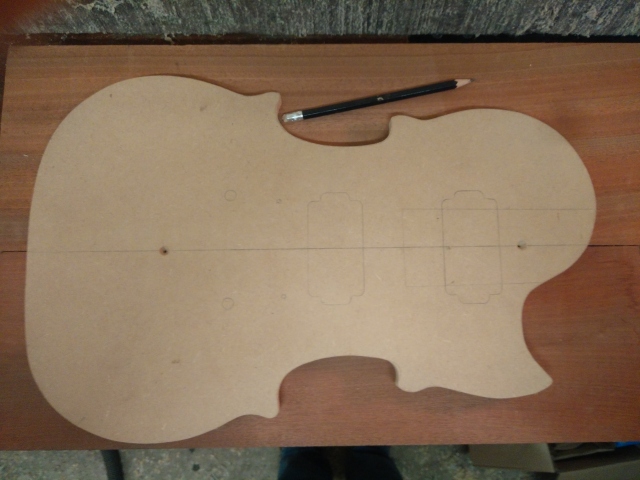

![IMG_20180407_111408[1]](https://tonyedwardsguitars.files.wordpress.com/2018/04/img_20180407_1114081.jpg?w=640)

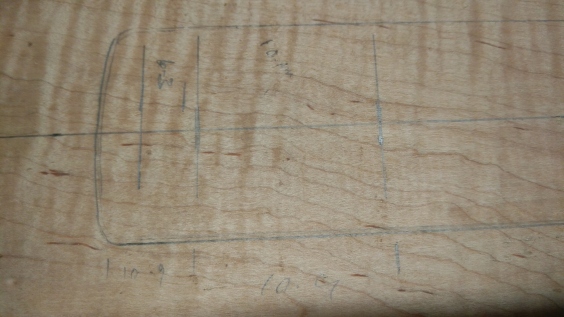

![IMG_20180407_134326[1]](https://tonyedwardsguitars.files.wordpress.com/2018/04/img_20180407_1343261-e1523115213307.jpg?w=640)

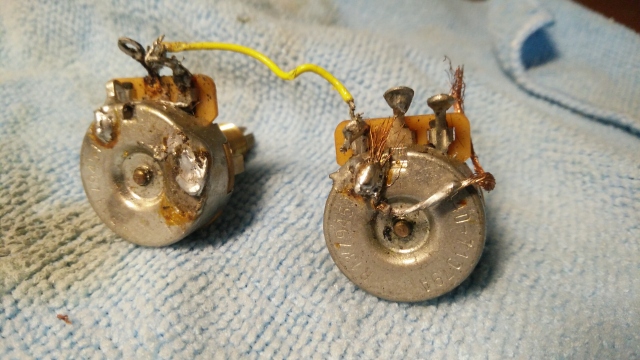

![IMG_20180407_111339[1].jpg](https://tonyedwardsguitars.files.wordpress.com/2018/04/img_20180407_1113391.jpg?w=640)

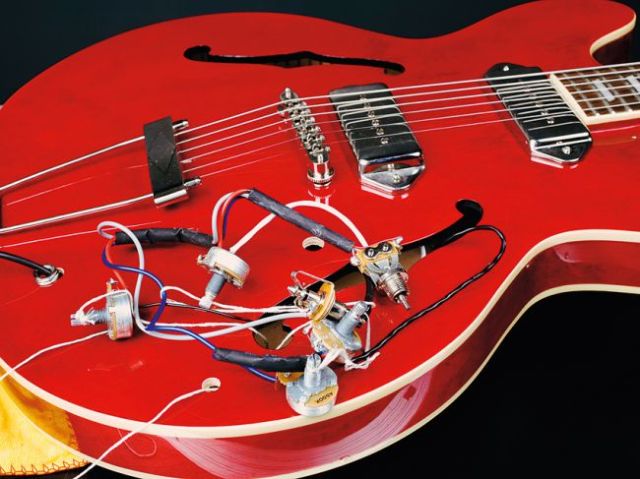

![IMG_20180407_114125[1] IMG_20180407_114125[1]](https://tonyedwardsguitars.files.wordpress.com/2018/04/img_20180407_1141251.jpg?w=316&resize=316%2C316&h=316#038;h=316&crop=1)

![IMG_20180407_114108[1] IMG_20180407_114108[1]](https://tonyedwardsguitars.files.wordpress.com/2018/04/img_20180407_1141081.jpg?w=316&resize=316%2C316&h=316#038;h=316&crop=1)

![IMG_20180105_113848[1]](https://tonyedwardsguitars.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/img_20180105_1138481.jpg?w=640)

![IMG_20180109_144533[1]](https://tonyedwardsguitars.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/img_20180109_1445331.jpg?w=640)

![IMG_20180111_111530[1]](https://tonyedwardsguitars.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/img_20180111_1115301.jpg?w=640)

![IMG_20180112_135751[1]](https://tonyedwardsguitars.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/img_20180112_1357511.jpg?w=640)

![IMG_20180131_113638[1]](https://tonyedwardsguitars.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/img_20180131_1136381.jpg?w=640)

![IMG_20170818_175422[1]](https://tonyedwardsguitars.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/img_20170818_1754221.jpg?w=640)

![IMG_20170812_094026[1]](https://tonyedwardsguitars.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/img_20170812_0940261.jpg?w=640)

![IMG_20170818_175413[1] IMG_20170818_175413[1]](https://tonyedwardsguitars.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/img_20170818_1754131.jpg?w=316&resize=316%2C237&h=237#038;h=237)

![IMG_20170818_175401[1] IMG_20170818_175401[1]](https://tonyedwardsguitars.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/img_20170818_1754011.jpg?w=316&resize=316%2C237&h=237#038;h=237)